France: a further step back for populism in Europe?

France: a further step back for populism in Europe?

“It is not certain that everything is uncertain.”

Blaise Pascal, Les Pensées, 1669

08 May 2017

Opinion polls got it right. After months of campaign, M. Macron becomes the President of the French Republic for the five years to come. Starting off with a short political career and a sheer 13% in the polls in November last year, he is now the resident of the Palais de l’Elysée with a large lead and a small “party” (a “movement” rather, as it is called). After the elections in Austria and the Netherlands, the French presidential election may be the marker a further step back for populism in Europe.

Between the two rounds: a decisive moment

The first round of the election placed M. Le Pen (21.3% of the votes) close behind E. Macron (24.01%) and before F. Fillon (20.01%), J-L. Mélenchon (19.58%), and B. Hamon (6.36%), thereby eliminating the traditional parties of government from the race. The Socialist Party notably, led by B. Hamon, scored very low and is the big loser of this election, thus heralding uncertain results for the party in the legislative elections to come. Two weeks after the first round, the French were called to the polls again and granted a clear victory to Emmanuel Macron (En Marche!) with 66.06% of the votes in his favour whilst Marine Le Pen (National Front) stalled at 33.94%.

These results come after a turbulent moment between the two rounds. The face-to-face TV debate between the two contenders on May the 3rd has regrettably marked the campaign (and the Vth Republic) for its low level of discussion. The far-right representative displayed a particularly aggressive stance, characterized by a mocking laughter and ambiguous allusions. Some observers even spoke of a Trumpisation of the election when she referred to “alternative facts” or emitted ill-founded allegations. A debate hard to moderate for the journalists, widely qualified as a bare-knuckles boxing match that brought very little to the important topics; immigration and Europe[1] for our purposes. A huge strategic mistake for a leader that has spent years to pacify the image of her party (let us recall that she excluded her father, the party’s founder, after he produced anti-Semitic comments) and that counted on conservative voters’ support for the second round. Most likely, this change of tone has definitively scared off the right-wing voters that would have reluctantly voted for her.

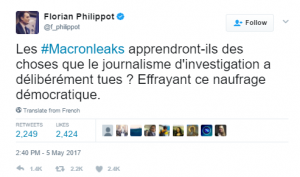

Another moment that marked the period between the two rounds is the hack of Macron’s collaborators’ email accounts and illegal disclosure of numerous campaign documents to which fake ones would have been added. Interesting fact, this massive number of documents was released little before the official end of the campaign – i.e., absolute silence for the media and politicians -, so that no analysis of the bulk could be done or publicized before the vote. Florian Philippot, high ranking National Front leader, announced the leak, thereby feeding the doubts looming over a possible scandal.

The legislative in prospect

The French President of the Republic is one of the most powerful heads of state in the world. France is a semi-presidential regime tailored by the General de Gaulle for himself with a view to curb the instability generated by the parliamentary regime of the French IIIrd and IVth Republics. The Vth Republic remains a democracy nonetheless; meaning it is characterized by a system of checks and balances. The French President is powerful, provided he can count on a majority in Parliament.

The first round of the election left in the race a party that is not a party (En Marche!) and a party that has never been in charge and that only recently ceased to be a party of contestation[2] (the National Front). How could any of the two have built a majority? To answer this question, the last bit of the race opened a risky game of alliances. M. Le Pen was rallied by N. Dupont-Aignan (4.7% in the first round), self-proclaimed Gaullist and renowned anti-European, first candidate ever to officially declare support to the National Front in Presidential election, whilst most other candidates invited to vote for E. Macron to form a Republican front in order to outflank the far-right candidate. A risky game that has well understood J-L. Mélenchon who refrained from supporting E. Macron, allegedly in the prospect of the legislative elections to come. In doing so, he established some sort of equality between the two candidates, placing himself as the only anti-system leader.

Indeed, the legislative elections of June 2017 is the next deadline, the moment in which the French will know what sort of five-year term is awaiting. As of yet, En Marche!, Macron’s movement, counts a limited number of public figures who can viably be elected MPs. Given his refusal of a coalition of parties, building a stable majority in the lower chamber may prove a difficult task. Without a coalition of parties, he will have to count on either individual adhesions to reforms or public figures joining his movement (which in most cases would imply they resign from their current political formation).

Tiny steps forward?

As of now, there are still quite a number of unknown variables concerning the legislative elections. Too many MPs for the National Front or for the France Insoumise (J-L. Mélenchon’s party) could very well hamper Macron’s agenda for the country. All the more so considering that his election is not exactly the manifestation of people’s adhesion to his programme. For both the first and the second rounds of the election, many French chose to vote for him as the candidate best capable of blocking the far right in a second round. Now that political parties are preparing for the legislative elections, the so-called “third round” of the presidential election, uncertainty reigns. One thing though is certain; Marine Le Pen has obtained more support than ever. There were 6.4 million people voting for her in the first round of the 2012 presidential election; they were 7.7 million for the first round this year, 10.6 million for the second round. We may think of a glass half full or half empty as we may think of a step back for populism or tiny steps further.

***

[1] M. Le Pen’s position on the EU and the Euro was particularly confusing for that matter.

[2] The National Front has long been a party of contestation with little pretention to exert power. One would remember the 2002 Presidential election and the feeble campaign led by Jean-Marie Le Pen between the two rounds. As Marine Le Pen, his daughter, argues: “The National Front was a party of contestation (…). Today, it is a party of government”.

SEE STRATEGIC LINE IMMIGRATION AND THE FUTURE OF THE EUROPE

English

English